Vases depicting “La fuite d’Elise” (left) and “Tom et Evangeline” (right), attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 19". (Courtesy, Museum of Arts and Sciences, Daytona Beach, Florida.)

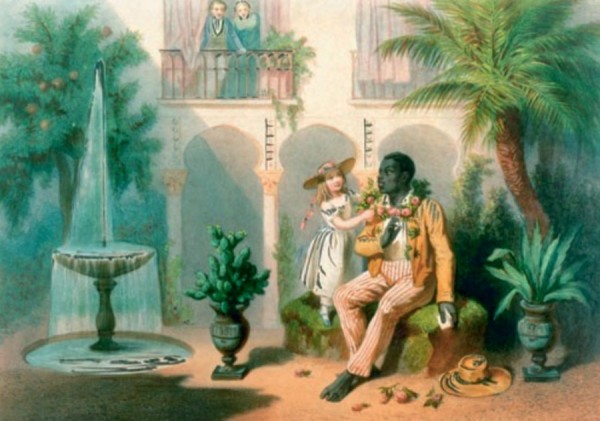

Charles Bour, “Tom et Evangeline,” lithograph, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, La case de l’oncle Tom, Paris, 1853. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.)

Joseph Bettannier, “La fuite d’Elise,” lithograph, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, La case de l’oncle Tom, Paris, 1853. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.)

Map of France showing locations of Limoges, Vierzon, and Paris. (Map, Wynne Patterson.)

Porcelain vase exhibited by Haughwout and Dailey at the Crystal Palace Exposition, 1853. From Benjamin Silliman, World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54 (New York: Putnam, 1854), p. 129.

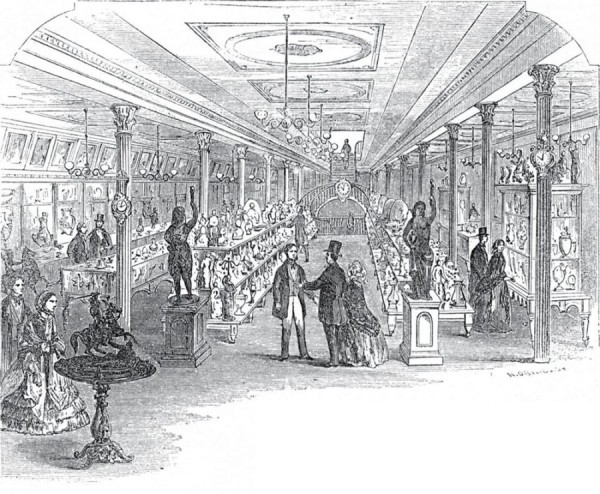

Nathaniel Orr and Company, “Saleroom, Main Floor, Haughwout Building, New York.” Wood engraving, reproduced in Cosmopolitan Art Journal 3 (June 1859).

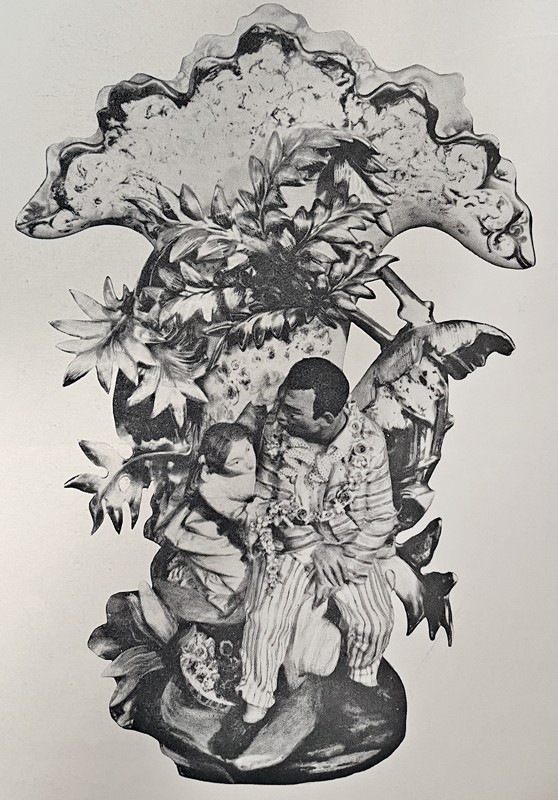

Vase depicting “Tom et Evangeline,” attributed to Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 19". (Illustrated in Stéphane Faniel, Le XIXe siècle français [Paris: Hachette, 1957], p. 92.)

Vase depicting “La fuite d’Elise,” attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 19". (Courtesy, Collection of Brooke Eastlick; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Vase depicting “Tom et Evangeline,” attributed to Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 19". (Courtesy, Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum; photo, Lawrence Mott.)

Vases depicting “Tom et Evangeline” (left) and “La fuite d’Elise” (right), attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 19". (Courtesy, Collection of Brooke Eastlick; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Vase depicting “Tom et Evangeline,” attributed to Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 19". (Courtesy, Collection of Brooke Eastlick; photo, courtesy of Freeman’s Auction House, Philadelphia.)

Vases depicting “La fuite d’Elise” (left) and “Tom et Evangeline” (right), attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.)

Vase depicting “Tom et Evangeline,” attributed to Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Collection of Brooke Eastlick; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Vases depicting “Tom et Evangeline” (left) and “La fuite d’Elise” (right), attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art.)

Vases depicting “La fuite d’Elise” (left) and “Tom et Evangeline” (right) attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, Albert Cousins Memorial Fund, and purchased as the gift of Ann Bosworth; photo, Mitro Hood.)

Candlesticks depicting “Tom et Evangeline” (left) and “La fuite d’Elise” (right), attributed to Hache et PépinLehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York, New York, 1853–1870. Biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Collection of Brooke Eastlick; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

SINCE “FRAGILE LESSONS : Ceramic and Porcelain Representations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was published in Ceramics in America in 2006, new discoveries regarding a group of French porcelain vases of Uncle Tom and Eliza that were prominently featured in that article have come to light, including previously unknown examples and the identification of their likely maker, the manufacturer Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur of Vierzon, France (fig. 1).[1]

Harriett Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or, Life Among the Lowly was first published in serialized form in 1851–1852 and subsequently as a two-volume novel in 1852. Intended by Stowe (1811–1896) to “paint a word picture of slavery,” it was an instant success, selling well over a million copies its first year.[2] The novel proceeds through scenes alternately sentimental and melodramatic, describing the lives of several enslaved individuals, the most prominent being Tom and Eliza. Stowe was criticized at the time— and since—for her stereotypical, sometimes racist depictions of the African American characters, but even so it was one of the earlier books written by a white author to depict enslaved characters with dignity and to show the Black family as being just as deserving of godly love and affection as anyone else.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was incredibly popular, and almost simultaneous with its publication came a variety of theatrical reenactments and interpretations. Those, in turn, resulted in the creation of a wide range of paintings, prints, sculptures, and ceramic figures that depicted the main characters and key moments of the novel.

Among the larger and more elaborate renditions of characters from Uncle Tom’s Cabin are a pair of French porcelain figural vases. Each vase combines an unglazed biscuit porcelain figural group set among glazed porcelain foliage and placed before a flaring, flat-backed vase of greater height. The vases depict two key moments in the novel that were also the most popular in dramatic and musical performances. One features Tom being draped in a garland of flowers by his then-owner’s daughter, Eva, capturing a moment of Christian compassionate love, with the innocent girl and the adoring, obsequious enslaved man drawn together by the arbor’s foliage (fig. 2). The other features Eliza, clutching her son, Harry, leaping from ice flow to ice flow as she escapes over the frozen Ohio River to freedom (fig. 3). The size of these vases, the quality of the materials, and the skill with which they were designed, modeled, and decorated—and the high price they almost certainly commanded—all point to the enormous cultural influence of Stowe’s novel.

Throughout this essay I use the French name for the characters on the vases, because they were made in France, and because the forms they take derive from one of the seventeen French editions of Le case de l’oncle Tom, published in 1853.[3] Specifically, Charles Bour (1814–1881) illustrated the scene of “Tom et Evangeline,” and Joseph Bettanier (1817–after 1877) illustrated “La fuite d’Elise.” Translated back into English, these titles read as “Tom and Evangeline” and “Eliza’s Escape” (figs. 2, 3).

E. V. Haughwout and Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur

I had previously suggested that the Uncle Tom’s Cabin vases were retailed by the New York firm of E. V. Haughwout. I since have found out that the figures were almost certainly made for Haughwout by the French firm Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, which had a factory in Vierzon, France, as well as a decorating workshop and saleroom in Paris. There was a long-lasting relationship between Haughwout and Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur that survived three iterations of Haughwout partnerships: Haughwout and Woram (1838–1852), Haughwout and Dailey (1852–1857), and E. V. Haughwout as a sole entrepreneur (1857–1870).

In an advertisement in the New York Evening Post that appeared on April 6, 1850, “TO THE PUBLIC | FRENCH CHINA WARE,” Haughwout and Woram made explicit their relationship with a porcelain factory in Vierzon, France.[4] In describing the entwined connection between the unnamed factory and the retailer, the text covered Haughwout’s French agent, the factory products available in the United States, and the New York decorating studio:

We are now receiving nearly all the china coming to this country from the well-known porcelain works at Vierzon, the most extensive establishment in France, employing over 600 workmen and producing the most graceful forms . . . [the] arrangements with this house enable us most assuredly to furnish China dining ware, tea ware, toilet ware, vases, clocks and every article made in porcelain at lower prices than any house in America. . . . We beg to state also, that we have established in connection with our house in New York, extensive works for decorating, painting and gilding China services. . . . [W]e have over 40 persons occupied in this branch, which number will be augmented to 80 or 100 after the first of May next. . . . [W]e are now receiving over 100 casks of the Vierzon China each month, which is sufficient proof of its quality, & c.[5]

Another advertisement in the New York Herald Tribune, published February 27, 1852, provides further information about the relationship, announcing the dissolution of Haughwout and Woram’s partnership in favor of a new one with William I. F. Dailey, effective February 2, 1852, through February 1857.[6] Woram, who was Haughout’s father-in-law, gave the business a $30,000 cash infusion (about $1.1 million today). The advertisement made clear, “the General Nature of the business to be Transacted is the Importing, Buying, Decorating, Dealing In and Selling Of China, Glass Lamps . . . House Furnishing and Fancy Goods. . . .”[7] Dailey brought further cash into the business, which allowed it to expand what it sold. In turn, the expansion consolidated Haughwout and Dailey’s place as one of the grand establishments selling table decorations, home furnishings, and luxury goods in New York City.

The Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur factory in Vierzon was owned by Adolphe Hache (1821–1917) and Léon Pépin-Lehalleur (1821–1899), who were brothers-in-law. The factory operated on the site of what had been Marc Schoelcher’s factory from 1829 to 1832. Schoelcher moved back to Paris and sold the site and works to Pierre Petry. Petry, the father of Adolphe Hache and Josephine Hache Pépin-Lehalleur, retired in 1845 and handed the factory over to his children.

One key to the factory’s success was its convenient location, halfway between Paris and Limoges (the procelain producing center of nineteenthcenturey France) (fig. 4). Another was the talent and business acumen of Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, under whom the factory thrived. Between 1845 and 1855, the number of kilns increased from three to seven, an enameling atelier was installed at the Vierzon site, and the number of employees grew from about 440 to nearly 1,000.[8] By 1855 they had established an enameling workshop and sales office in Paris at 24, rue de ParadisPoissonnière, a fashionable area near other luxury ceramics and glass manufacturers and retailers.[9]

The factory produced a wide range of table wares, toilet sets, and vases, receiving accolades for quality and design; at the 1855 Paris Exposition Universelle it was awarded the silver medal (prix d’argent) for designs of table and toilette services, cabarets, and “vases de porcelaine unie ou décorée.”[10]

Hache et Pépin-LeHalleur was an efficient operation, as it could take an item from design to completion. It could also deliver whiteware to Paris, enameled or gilded to order there or shipped plain to New York, where the porcelains could be decorated by painters at Haughwout’s studios on Broadway. The American ceramic historian Edwin Atlee Barber noted of the Haughwout and Dailey output, “As the ware so decorated was imported, it is not now possible to identify pieces bearing the work of this firm, unless obtained through persons who procured them direct from the decorators at that time and can vouch for their authenticity.”[11]

Although their wares were rarely marked—and to date no marked vases have been identified—there are stylistic similarities between the vase Haughwout and Daily displayed at the New-York Crystal Palace in 1853 (which Benjamin Silliman illustrated in his World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54) and aspects of the Uncle Tom’s Cabin figural vases, particularly in the treatment of the foliage to the side and the form of the upper mouth of the vase, as well as the gilt and enamel painting below the upper edge (fig. 5).[12]

In 1857 Haughwout moved his new emporium to the notable cast iron building designed by John P. Gaynor at 433 Broadway.[13] Ever interested in a gimmick that would help sales, Haughwout had America’s first passenger elevator installed in the building. In a review following the opening day of business, the New-York Daily Times reported, “[the store was] crowded with ladies and gentlemen admiring the immense variety of . . . china and porcelain, sighing for the statuary, valuing the vases. . . . Strangers will reckon Haughwout’s one of the institutions, for the marvels it reveals.”[14] In the new business, Haughwout’s kept up its connection to Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur. An 1857 advertisement stated: “Our friends . . . Mssrs. Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur, Vierzon, France, manufacturers of Porcelain . . . have devoted many months in the production of new and beautiful designs” (fig. 6).[15]

The dissolution of Haughwout’s partnership with Dailey in 1857 leads to one question: what happened to old, undecorated stock? According to Edwin Atlee Barber, “Mr. Daily with a new partner opened a decorating shop on Broadway, taking with them some of the painters of the original firm. The latter subsequently started decorating works on Greene Street, where Mr. Edward Lycett joined him.”[16] In the same issue of the NewYork Daily Times that notes the opening of E. V. Haughwout’s new store premises at 433 Broadway, a second advertisement confirms that Dailey had premises at 681–683 Broadway in which he was selling a portion of the stock from the old Haughwout and Dailey partnership, including, “Decorated china vases (usu $12) at $7.50.”[17]

Even after E. V. Haughwout closed in 1870, another retailer, Nicol and Davidson, bought out its stock and claimed itself successor.[18] Advertising in The Season as well as in Harper’s, the company aimed to absorb a large share of Haughwout’s old business—yet with a more developed scheme regarding interior design, mentioning last but not least items “Made in all colors to match furniture or room decoration.”[19] Thus, it is possible that some of the Uncle Tom’s Cabin porcelain vases were painted at Dailey’s or at Nicol and Davidson’s premises between 1857 and 1870.

The Vases

The vases were made in two heights—19 inches and roughly 11 1/2 inches— and were decorated in different ways, from undecorated biscuit with gilding highlighting the glazed porcelain foliage and vase, to ones that are richly enameled and gilded. In 2006 five pairs of large vases (one missing its mate) and four pairs of small vases were known, each decorated differently, which at the time was thought to reflect American merchandisers’ wanting to present consumers with choices or custom orders.

Since then, we now know of fourteen pairs of large vases (one of which is represented by a single vase) (figs. 1, 7–11) and eight pairs of small vases (figs. 12–15). A pair of candlesticks with the same figures as those found on the smaller vases has been discovered as well (fig. 16).

The decorative scheme of several of the newly discovered vases matches previously known examples, suggesting that the vases were not decorated to order, but rather were done in batches or by different decorators working in different styles.

In one group of the large vases, currently represented by seven pairs, the foliage and vases are elaborately gilded and the figures are painted in polychrome overglaze enamels with patterned clothing, including striped pants on Tom (figs. 1, 7, 9).[20] There are variations in the details of the clothing: in most Tom wears red-striped pants, but in two he wears blue pants, and the pattern on Eliza’s dress differs from vase to vase.

The fact that one pair—known only through an illustration in Le XIXe siècle français by Stéphane Faniel, a 1957 work on French decorative arts— was in a private collection in France suggests that it had always been in France, and thus was likely to have been decorated in France, presumably at either Hache et Pépin-Lehalleur’s factory in Vierzon or in the decorating studio in Paris (fig. 7).

In the second group of large vases, currently represented by five pairs, the bisque porcelain figures are left in the white, and the glazed porcelain vase and foliage are either gilded or gilded and enameled (figs. 10, 11).[21]

There are currently eight pairs of the smaller (11 1/2" tall) vases known, showing four different types of decoration.[22] In one group, the vases and foliage are gilded and the figures painted in polychrome enamels, though the two examples currently known are painted differently (fig. 12).[23] In the second and third groups the bisque figures are either enameled or left in the white, while either the palmette leaves or the banana leaves are enameled as well as gilded (figs. 13, 14).[24] In the final group the figures are in the white and the vases and foliage enameled or gilded (fig, 15).[25]

In addition to the vases, a pair of candlesticks have been identified, featuring the same figures as the smaller porcelain vases, but they support candlestick nozzles instead of vases (fig. 16). The enameling to the biscuit porcelain figures is identical to that of the great majority of the larger vases. A painted calico skirt on Eliza’s figure appears on the “La fuite d’Elise” candlestick, while the “Tom et Evangeline” candlestick is painted with Uncle Tom wearing a horizontal striped jacket over vertically striped pants, like pajamas. All the flowers in the garland are polychrome painted, and both candlesticks are painted with familiar gilt scrolls and whirls under the gilt band edge.

These vases and candlesticks are among the more elaborate objects made to capitalize on the global popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The newly discovered examples of the vases and the candlesticks suggest that while there is still a great deal of variety among the vases, at least some seem to have been decorated together at the same place—and that at least some of the vases were likely decorated in France. This new information expands and enriches both our understanding of these objects and the cultural power of Stowe’s novel.

Jill Weitzman Fenichell, “Fragile Lessons: Ceramic and Porcelain Representations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 40–57.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin: A Moral Battle Cry for Freedom, 2023, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, https://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/harriet-beecher-stowe/uncle-toms-cabin/.

In the mid-nineteenth century, unauthorized publications of popular novels were quite common; printers took advantage of a novel’s popularity as quickly as possible after authorized editions appeared.

“To the Public | French China Ware,” New York Evening Post, April 6, 1850, p. 2, col. 7.

Ibid.

Dailey’s middle initial is given variously as an I or a J, and his surname is spelled variously Dailey and Daily.

New York Herald Tribune, February 27, 1852, p. 3, col. 4.

Xavier-Roger-Marie Chavagnac and Gaston-Antoine Grollier, Histoire des manufactures françaises de porcelaine (Paris: A. Picard et fils, 1906), p. 694.

The location was very near to the porcelain factory of Jean-Baptiste Gille, known as Gille Jeune, at 28, rue du Paradis-Poissonnière, which had opened in 1836; it was also adjacent to the Paris distributorships of the luxe crystalleries Baccarat and St. Louis, located at numbers 30–32. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen wrote, “A hotel-ware plate in a private collection carries a mark for E.V. Haughwout with both a Broadway address and a Parisian one, ‘24, R. de Paradis Poissre,’” in Art and the Empire City, New York 1825–1862, edited by Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), p. 330, fn. 13.

Les arts chimiques à l’Exposition universelle de 1855 (Paris: N. Chaix, 1856), p. 224, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1025139g?rk=21459.

Edwin Atlee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), p. 215.

Benjamin Silliman, World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54 (New York: Putnam, 1854), p. 129.

Now a landmark, and still called the E. V. Haughwout Building.

“The Opening of E.V. Haughwout’s New Store,” Special Notices Section, New-York Daily Times, March 17, 1857, p. 5, col. 3.

Syracuse Daily Standard, March 27, 1857, as mentioned in the White Ironstone China Association E-News 2, no. 4 (October 2021), pp. 2–4, https://www.whiteironstonechina.com/docs/202110-enews.pdf.

Barber, Pottery and Porcelain, p. 183.

“Down They Go! Down They Go!!,” Special Notices Section, New-York Daily Times, March 17, 1857, p. 5, col. 6.

Nicol and Davidson, brothers-in-law in business since 1835, had their showrooms at 686 Broadway, three doors down from Dailey’s, as well as in Paris at 35, rue d’Hautville. Their factory was at 4 Great Jones Street

The Season 7, no. 1064 (September 28, 1870): 1, col. 3; Harper’s Weekly, no. 14 (October 1, 1870): 640.

These include a pair of figures at the Museum of Arts and Sciences (Daytona Beach, Florida), a pair at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center (Hartford, Connecticut), a pair at the Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum (Harrogate, Tennessee), two pairs in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick (Florida), a pair in a private collection, and a pair in the collection of Mme Gabrielle Lorie, published in 1957 (present whereabouts unknown).

These include two pairs with just gilding at the Newark Museum (Newark, New Jersey) and in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick, a pair with purple enameling on the vases at the Reeves Museum of Ceramics (Washington and Lee University), a pair with blue enameling on the vases in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick, and a single figure of Tom with red enameling on the vase in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick.

These include a pair at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, a pair at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston, Texas), a pair at the Newark Museum, a pair at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art (Memphis, Tennesee), a pair at the Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore, Maryland), and three pairs (one represented by just one vase of Tom and Eva) in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick.

These include a pair at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, a pair at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and a pair in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick.

These include a single vase of Tom and Eva with blue veining on the palmette leaf, green veining on the banana leaf in the pair at the Newark Museum, and red veining on the pair at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art.

These include a pair of vases with pink enamel and gilding in the Collection of Brooke Eastlick and a pair with just gilding at the Baltimore Museum of Art.